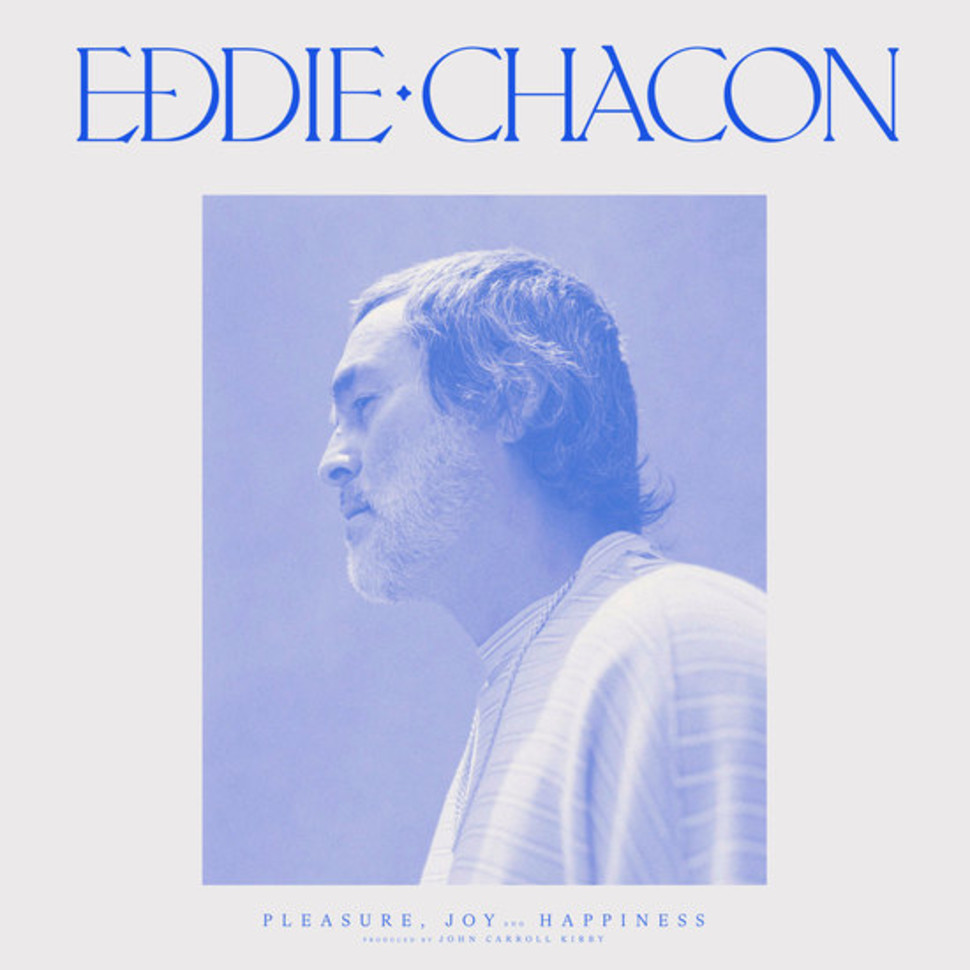

Eddie, you haven’t recorded music for ten years. Why was now the right time to go back into the studio?

I had the opportunity to have coffee with John Carroll Kirby and we just clicked. We seemed to see eye to eye on so many things musically. It just felt right. We were introduced by the owner of TERRIBLE RECORDS (a mutual friend) that had a hunch we’d have chemistry. Thank you Ethan.

How did the collaboration work?

Sometimes he’d have a track for me to sing to. Sometimes I’d come with a song that he’d create a track for. We’d polish things together sometimes in person. Sometimes in texts sent all hours of the night.

Your album is very minimalist. Besides Kirby, only Kanye West’s Sunday Service drummer Lamar Carter accompanied you. That makes it sound very intimate.

Kirby already had a very meditative minimalist sound that he’s carved out for himself. I didn’t want to stray from the beauty of that. It suited me just fine.

Where was the album recorded?

It was recorded in Kirb’s studio on the edge of downtown LA. It’s a very chill space with a nice kitchen. I spent a lot of time watching John make meals or coffee for us. We had a lot of good conversations in that kitchen. I think those conversations were important to the creation of the record.

Even if “Pleasure, Joy and Happiness” is not a typical retro-soul album, the soul in your music is unmistakable. The songs go deep. Does the recording of the album also have a therapeutic dimension for you?

I’m always surprised myself at how where I’m at in my head / what I’m working through at the time does seem to make it way into my lyrics and the feel of my music.

You said: “If I have a clear head, I can make a record where I am honest with myself.” How important is honesty and authenticity for you as a musician?

I think you’ve got to capture your world authentically or it’s just not engaging. People gravitate toward a good story. The best story’s to me are autobiographical.

When I heard the album for the first time, I couldn’t help thinking of the late great Marvin Gaye. Maybe that would have been the sound he would have chosen nowadays. How important is Marvin Gaye’s music for you? What other sources of inspiration did you have for the album?

Marvin Gaye is certainly a favorite of mine. I often refer to his music when I feel I’m a bit out of sorts. The purity of his music seems to realign me with myself.

When I was younger Leon Ware (producer of the Marvin Gaye “I Want You” record) was a mentor of mine. I still regret not asking him more questions about his time with Marvin. I was inspired by a lot of instrumental music while making the record.

Did the pandemic have an influence on the music?

We made the record before the pandemic but I was deeply disturbed by the pace and chaos of the world at the time and felt a deep need to create something kind. A break from the chaos so to speak.

Eddie, you grew up in Castro Valley, Northern California, as the youngest of three boys. What role did music play in your parental home?

Music was everything in our house. My brothers and I all played in a marching band as kids. We were obsessed with James Brown, Al Green, The Jackson 5, Diana Ross but also Led Zeppelin, Robin Trower, Rick Derringer and Todd Rundgren.

Is it true that your father wanted you to be a singer?

I found out much later that my father loved Johnny Hartman and wanted to be a singer. He was quite hard on me but in a very caring way when I’d sing as a kid. He really stressed the importance of timbre, intonation and pitch.

Eddie, in your first garage band you played together with Faith No More drummer Mike Bordin and the legendary Metallica bassist Cliff Burton. What a line-up! How did that come about and what kind of music did you play?

We were kids and we played Black Sabbath and Aerosmith covers. We grew up in the same neighborhood. Mike was a really good childhood friend and Cliff was Mike’s really good friend. We rehearsed in the front lobby of my folks trucking company. It was in a industrial park so we could play as loud as we wanted. Those guys were already incredible musicians. I was a little younger and still finding my way. They were tough as hell but damn I learned a lot.

I have to ask this: how do you remember Cliff Burton?

Cliff was incredibly focused and incredibly direct. The three of us were extremely serious and passionate about our music. It was friendly but those two definitely had zero tolerance for error or bullshit.

You already started writing your own songs at the age of twelve. Did you know early on that you wanted to become a professional musician?

Yes. It’s how I saw myself and my life for as long as I can remember.

After school, you moved to LA and started sending out demos. You got a solo deal with Columbia when you were just 20. How do you remember your first steps in the music business?

I was extremely coddled. I somehow fell under the tutelage of a very nurturing team of music executives at CBS who knew I was basically alone in LA.

They fed me, introduced me to every legendary artist I grew up idolizing and put me in the studio to observe some of the greatest songwriters of our time. I was very blessed. The CBS offices were like a home to me. I literally hung out there everyday. They were family.

You also worked with the legendary Dust Brothers. How was that collaboration?

Mike and John were cool as a cucumber. Those guys made it look so easy I couldn’t even see what they were doing. I loved those guys. They had a cool house in the hills with a swimming pool. We smoked weed. We swam in the pool. Lots of great artists came and went. They were a lot of fun to make music with. We hung out in LA and NYC on the late 80’s.

Finally you went to New York, signed with Capitol and met Charles Pettigrew. Please tell us a little bit about that fateful encounter.

It was just another incredibly fateful encounter. We struck up a conversation on a NYC subway train. We were both signed to Capitol but we didn’t know it at the time. We were even signed by the same A & R guy. At that time we both had first right of refusal deals. Thats where the record company reserves the right to change their mind if they don’t like what you create.

Shortly after that, you started writing songs together. In 1992, your song “Would I Lie to You” was finally released and became a worldwide No. 1 hit. From todays perspective, what is your relationship to this song that overshadowed your career?

My father was a truck driver. I came from a working class family. I was fortunate that I got do anything artistic at all. I still pinch myself everyday honestly.

This world didn’t owe me anything. I was just one of countless people who had some talent. I grew up with musicians far more talented then I. I was lucky to say the least. I get a real kick out of everything that somehow happened to me.

What happened to Charles & Eddie after this world hit?

After 5 years of nonstop travel we needed to get back home. It was a dream come true but it was also exhausting. We went our own ways and just kind of never came back together except shortly before Charlie died. We were panning a record.

In 2001, Charles died of cancer at the age of 37. How do you remember him as a person and musician?

I loved Charlie so much. He was sweet but he was direct as hell and tough as nails. He was my musical partner but damn I learned so much from him. I find the best people are more concerned with making you better then sparing your feelings. He was that kind of guy.

In the early 2000s a gift finally opened up a different career for you: a friend gave you a camera. You became a successful fashion photographer and creative director. What excites you about photography and fashion? Also pictures tell stories: are there certain similarities with your work as a songwriter?

It was a much needed creative outlet for me when I walked away from music. It felt just like songwriting to me. Just another way to tell a story.

What will happen next for Eddie Chacon? Are you already thinking about another album?

I’m excited to make another record. It feels fresh again to be making music after so many years away.

Eddie, thank you very much for the interview.

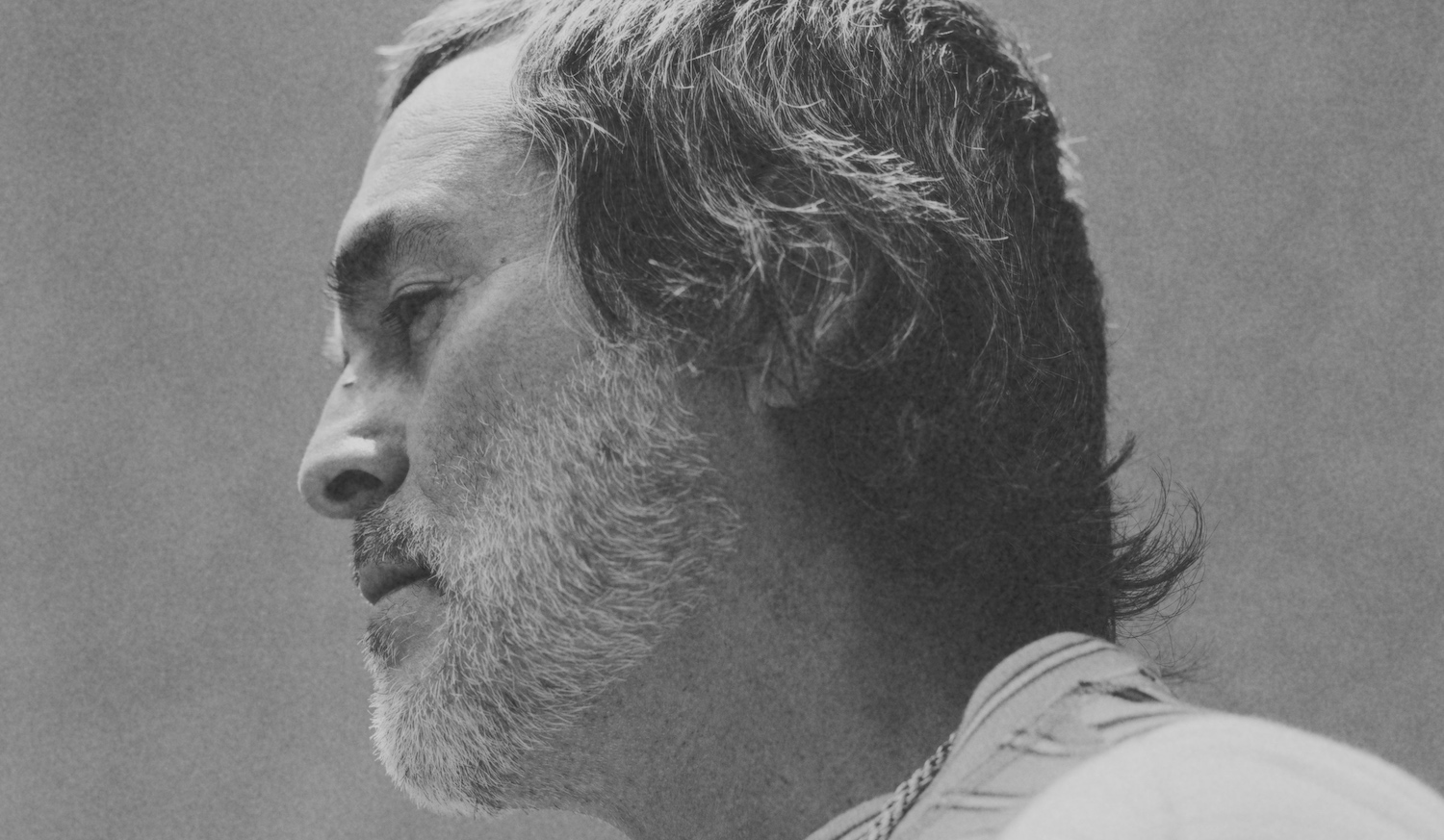

Photo: Bennet Perez